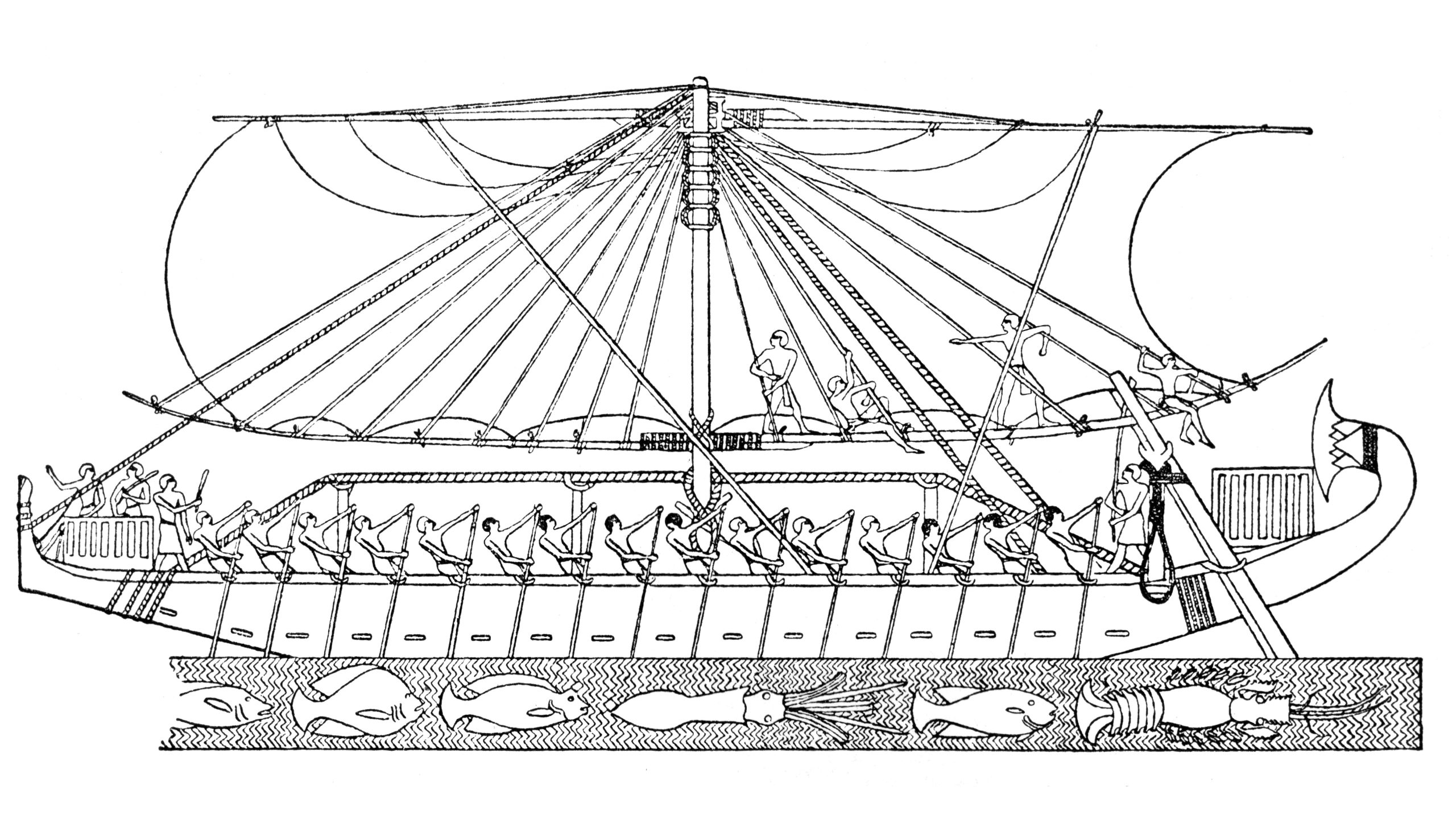

Sometime between 1213 and 1203 BC, four hundred and fifty years before the founding of Rome, Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah sent aid relief to the Hittite Kingdom during a time of famine. It wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last during the late bronze age, that humanitarian aid would flow across borders in friendship in the form of food, textiles and more. (Cline, 2021, pp. 154-157)

Egypt and the Hittite Kingdom were two of the superpowers of their age, sometime at war, sometime on friendly terms. I don’t know about you, but learning that more than three thousand years ago, empires would come to each other’s help in times of need definitely came as a surprise to me. It’s not that there’s anything inherently improbable about it, when you think of it. After all, they were humans just as we are, with all the strengths and failings that characterize us today as a species. It’s simply that it had never occurred to me that something as modern as international aid might have existed three thousand years ago.

In his remarkable book1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed, Eric H. Cline, a professor of classics and anthropology at George Washington University, draws a fascinating account of the bronze age, a period that extended over two thousand years, as a surprisingly interconnected and interdependent world with dynamic trading networks moving goods and ideas, at sea and on land, across vast distances and many civilizations.

It all came to an end towards the end of the 12th century BC as a result of “a perfect storm of calamities”, in Cline’s words, ranging from earthquakes, internal rebellion, migratory movements, disease, drought, crop failures, a collapse in trade, and more. “In the end”, he writes, “it was as if civilization itself had been wiped away in much of this region. Many, if not all of the advances of the previous centuries vanished across great swaths of territory, from Greece to Mesopotamia.” (Cline, 2021, p. 9) In many places, it would be centuries before civilization would attain again its previous level of wealth and complexity, a story that Cline told in 2024 in his equally fascinating follow up book, After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations.

As I was mentioning above, we are the same species that walked the Earth thousands of years ago and while it may be tempting to think that we are somehow better or improved from our predecessors, the differences we observe around us are the result of advances in science and technology, not biology.

Whether or not we have progressed in matters of morals and ethics is an open question. According to evolutionary biologist Nichola Raihani of University College London, collaboration is our species’ undisputed superpower. “Humans”, she writes, “are one of the most cooperative species on the planet… We aren’t the only species that helps strangers, but we do it on a scale that is simply unparalleled in the natural world.” (Raihani, 2021, p.126)

Collaboration indeed – an idea that is predicated on the belief that we can do better together than we would ever do on our own. Now surely, collaboration doesn’t require the idea of collaboration, or a belief in its benefits. After all, other species collaborate (meerkats, for instance) and nobody would suggest that they have given much thought to it. For them as for us, there is something hard coded about it. But contrary to other animals, we humans are endowed with the ability to reflect on the consequences of our actions and to make choices that go against our baser impulses. It is our ability to apply our powers of reasoning to incredibly complex problems – including in fields such as law, ethics, and politics – that has allowed our species to take collaboration to an entirely different level.

“The quintessential repeated transaction”, writes Raihani, ”is a friendship”. (Raihani, 2021, p. 137) The ancient Greeks – those that lived in the Classical period hundreds of years after the collapse of the bronze age civilizations previously mentioned, had a much broader definition of friendship than we do. The ancient conception of friendship encompassed realities as diverse as the friendship of pleasure between two drinking buddies, the unequal friendship of parents and children, the friendship of excellence between a teacher and a student, and a wide range of friendships of utility, from merchants entering into trading transactions, to partners in a business venture, to citizens of a city held together by feelings of concord (a form of friendship). (Pangle Smith, 2003)

For Raihani, from the standpoint of an evolutionary biologist, the key question is to understand “why it might be advantageous to help someone else to whom you are not related, even if they don’t always help you in return.” (Raihani, 2021, p. 137) The answer, it turns out, is that the ability to collaborate in this way increases the probability that you will make it. It’s not a zero-sum game. If you and your blood relatives are able to thrive in perfect autarky, perhaps you don’t need to collaborate with strangers. But if challenges to be faced are on a different scale – city, country, continent, or planet – then we can only thrive (and indeed, survive) together by leveraging our superpower of collaboration on ever-greater scales. As a species, this is our collective challenge.

Three thousand years ago, empires came to each other’s aid in a spirit akin to our modern idea of “friendship among nations”. Facing today challenges on an unprecedented scale, will we choose friendship and collaboration, or sterile confrontation?

References

Cline, Eric H. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2021, 277 pages.

Smith Pangle, Lorraine. Aristotle and the Philosophy of Friendship. Cambridge University Press, 2003, 255 pages.

Raihani, Nichola. The Social Instinct: How Cooperation Shaped the World. St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2021, 304 pages.